The City of Charlottesville resembles the best of a rural college town despite its problems. Economically, the town depends on balancing the relationships and interests of students with its residents. Historically, issues of racism, opportunity, class, crime, and politics have embroiled the city and the campus of the University of Virginia as deeply as the recently revealed DNA connections between Thomas Jefferson and the enslaved Sally Hemmings. These truths about Charlottesville have always been known yet all too painful to acknowledge publicly, at least until recently.

Charlottesville recently became a dangerous and symbolic meeting place for white male outrage masquerading as resistance to the removal of a confederate statue. But it could have easily been one of any one of the other “Charlottesvilles” in the U.S. – Richmond, New Orleans, Lexington, Charleston, or Austin to name just a few where confederate statutes still exist and time delayed questions about our racial, gender, ethnic, and religious symbols have evoked emotional dialogue if not outright change.

Take, for example, the killings at Mother Emmanuel in Charleston, South Carolina, two years ago which, later on, did more than bring down a confederate flag whose presence above the court house had weathered efforts to remove it for decades. It erased a century of doubt that the racial status quo could not change.

Incidents like these other Charlottesvilles have raised similar public consciousness to reexamine old truths, overt contradictions, and widespread discrepancies. The white men who came from near and far to Charlottesville sought to reverse the city’s introspection and reimpose policies of male dominance and privilege. They sought to use confrontation, weaponry, intimidation, threats of violence, and worn-out symbols to maintain an environment marked by anti-Semitism, racism, sexism, and fear. They believe that the current national mood favors a return to a period in which any recognizable difference in people, whether it be color, language, religion, immigrant, sexual orientation, disqualifies one as American.

And that is precisely the problem. What is beneath their public armor and outrage is their anxiety, suspicion, and fear that removal of confederate statues foretells not only the decline of their ability to define who is and who is not an American but predicts their own removal.

The nation is certainly in flux, but there is no plan, process, policy, or procedure to discriminate against, segregate, or eliminate white men. The American promise is sufficiently grand to accommodate each of us as citizens, contributors, and participants. Violence as a means of controlling the rights of one’s fellow citizens is anathema to the principles of democracy found in our constitution. Those who have used violence, exploitation, and control in support of an illegitimate cause often fear retribution using the same methods they have employed.

We must identify and support more Charlottesvilles in the future, in which difference is acceptable and not debated. We must use their bravery as a spur to recreate the nation one Charlottesville at a time. It means we must reinforce that the nation’s law declares the Ku Klux Klan a domestic terror organization and ban it once and for all. At the same time, we cannot ignore the need for more open dialogue about the long-term deepening suspicion that underlies the current national mood and willingness on the part of some to secede rather than compromise, cooperate, share, and find common ground. We can and must address this historical male survival anxiety that lies hidden underneath so much of the behavior that we saw recently in Charlottesville and many other U.S. cities before that. Otherwise, the next violence will arise at a not too distant place and time to our own peril.

—

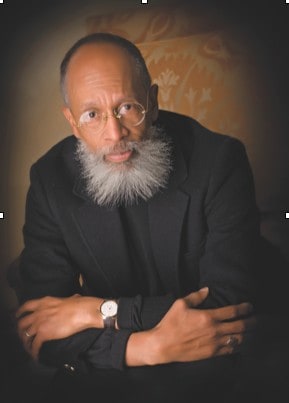

King Davis is a professor emeritus of African and African Diaspora Studies and a retired professor of social work at The University of Texas at Austin. This opinion piece was produced for Texas Perspectives and represents the views of the author, not of The University of Texas at Austin or the Steve Hicks School of Social Work. Versions it appeared in the Austin American-Statesman.