Persistent disparities in health between African Americans and whites begin at birth and may be partially explained by long-term residential segregation.

Persistent disparities in health between African Americans and whites begin at birth. Compared to white women, black women in the United States experience substantially higher rates of adverse birth outcomes, such as delivering low-weight babies and preterm births.

“We know that adverse birth outcomes are associated with infant mortality, morbidity and with social outcomes like low socioeconomic attainment,” says Catherine Cubbin, the associate dean for research at the School of Social Work. “Disparities in early life may have particularly devastating repercussions for the wellbeing of the black population over the life course.”

Health risk factors at the individual level, such as smoking or suffering from chronic diseases, do not consistently explain the racial disparities in adverse birth outcomes. Researchers have thus started to examine broader social factors, including the neighborhoods where people live.

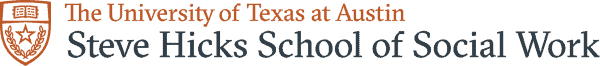

“There are high levels of residential segregation between blacks and whites in our country, which is partially a result of institutional discrimination in the housing market. It’s not just that black and whites live separately from one another: compared to whites, blacks tend to live in neighborhood environments that on average are more damaging to health,” Cubbin says. “So it is possible that the racial disparities in health may be at least partially explained by the black population’s cumulative exposure to neighborhood disadvantage.”

When it comes to operationalize neighborhood environments, most studies use static measures, such as the poverty rate at a certain point in time. But neighborhoods are not static: they evolve over time in response to economic, social, and political forces. Thus, a neighborhood’s history — rather its features measured at one point in time —may have differential impacts on health

With funding from St. David’s CHRP, Cubbin and Shetal Vohra-Gupta along with social work doctoral student Yeonwoo Kim are bringing the histories of neighborhoods into the analysis of racial disparities in birth outcomes.

They will use 40-years worth of census tract-level data—from 1970 to 2010— to reconstruct the socioeconomic histories of Texas neighborhoods, looking at characteristics such as long-term economic growth and deterioration. They will then compare those historical socioeconomic trajectories to point-in-time measures for 2010 in analyses of racial disparities in birth outcomes. Finally, they will use a critical-race-theory lens to examine the impact of public policies on black vs. white birth outcomes during the same 40-year period.

“We hope to shift the way researchers think about neighborhood context and health so that future projects taken into account long-term historical changes as well as who and what are accountable for those changes,” Cubbin says. “And moreover, by identifying Texas neighborhoods that are particularly detrimental or beneficial for birth outcomes and understanding why is that the case, our project has potential to inform interventions that will decrease black/white health inequities in our state.”

__

Posted June 21, 2017. By Andrea Campetella