When Caleb and Jeanette’s daughter, Rebecca, was murdered by her husband, it felt as though their lives had come to a crashing halt. How could they have missed the signs? How could they have failed to protect their daughter? What was “justice” in this situation? Although the police were immediately suspicious of David, Rebecca’s husband of three years, nearly six weeks went by before they had enough evidence to arrest him. During that time Caleb and Jeanette were advised to “play it cool” and not do anything that might make David leave the city. As if that wasn’t hard enough, they had to stand helplessly by while David dismantled his and Rebecca’s apartment, her precious things disappearing one by one.

Homicide charges were eventually filed and the District Attorney began to put its case together. When Caleb and Jeanette were contacted by a Victim Outreach Specialist on behalf of the defense attorney, the only thing they could think of that the defense might be able to help with was the recovery of their daughter’s Bible. David had to know where it was – but they had no access to David now charged with Rebecca’s murder.

The defense attorney was willing to explore the Bible’s whereabouts with his client. At first David denied knowing anything about it, then he said he’d probably thrown it out. But after several conversations with his attorney David finally suggested that it might be in box of personal things that he had left with a friend to store. That information was conveyed to Rebecca’s family and they were able to get Rebecca’s Bible back as well as other personal items that they treasure.

The Victim Outreach Specialist that helped Caleb and Jeannette is part of Defense-Initiated Victim Outreach (DIVO), a program administered by the Institute for Restorative Justice and Restorative Dialogue (IRJRD) at the School of Social Work. As Caleb and Jeannette’s case illustrates, DIVO provides a bridge between crime victims and their families and the attorneys who represent the defendant, especially in capital cases.

DIVO was born out of the ashes of the Oklahoma City bombing, when the defense wanted to reach out in some way to survivors and to acknowledge the depth of their pain and suffering. DIVO was created with the goal of reducing unnecessary tension with the defense for victim survivors and other crime victims who already bear the brunt of the crime.

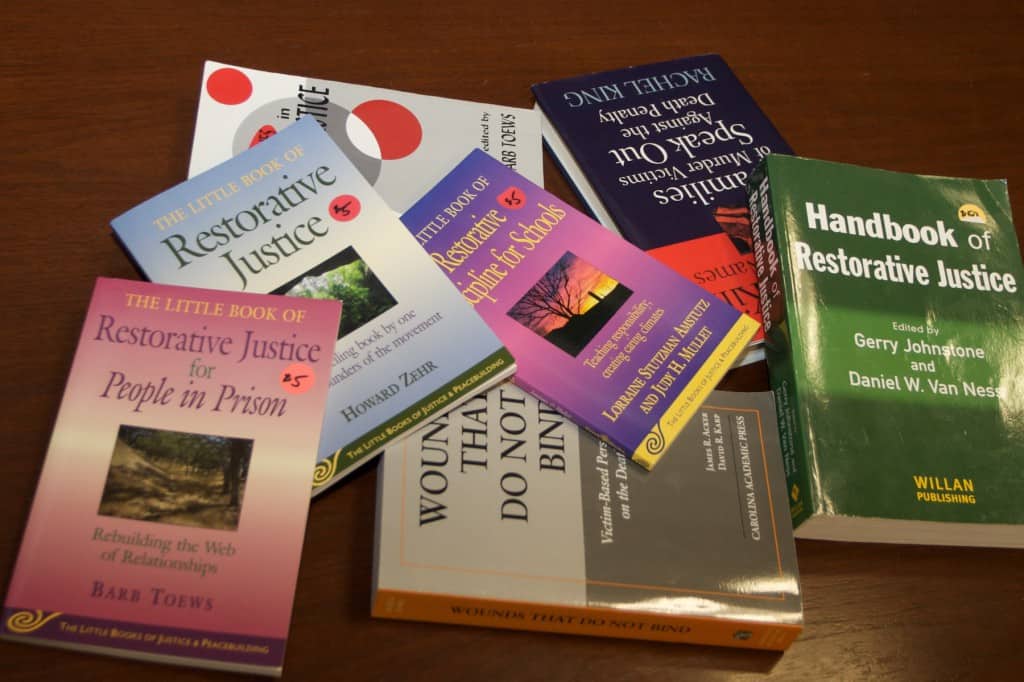

DIVO is based on restorative justice principles. As Dr. Marilyn Armour, IRJRD’s Director explained, restorative justice is a victim-centered response to conflict, crime and victimization that give the individuals most directly affected the opportunity to be directly involved in responding to the caused harm. “Punitive justice asks what laws were broken, who did it, and what punishment they deserve,” said Armour. “From a restorative justice perspective, the relevant questions are who has been hurt by the event, what are their needs, and whose obligations are these.”

The positive impact of DIVO was recently recognized by the Texas legislature when it passed HB 899. The most important provision of this law directs judges to contact victim survivors with information about the program. With the court being the first point of contact, information about DIVO is provided by a neutral source with credibility in the minds of victim survivors.

Restorative practices are not limited to criminal justice contexts. IRJRD is leading initiatives based on restorative justice principles in the areas of school discipline, domestic violence and, most recently, containment of open drug-dealing markets.

The Drug Market Intervention is a recent program in the city of Austin by which non-violent dealers are given the chance to get services such as drug rehab and housing as long as they don’t re-offend and make amends to the community they have offended (watch a recent CrimeWatch story in Fox News 7 about this intervention).

“Coordination among police, the district attorney’s office, and the community has been key to making this program work,” explained Armour. “From experience with other restorative justice programs for youth and minor crimes, we know that about a third of the offenders do not recidivate. This is a clear sign of the success of these programs. We do hope that our initiatives and research encourage others to embrace restorative justice principles and solutions for the many social problems our country faces.”