Social work researchers study patterns of substance use and abuse.

This is the third article in the series, “Celebrating 40 years of doctoral education and research at the School of Social Work, 1974-2014.” See previous articles here.

Have you ever tasted Tostilocos (recipe here)? Or danced to Nortec (listen to a sample here)? They are just two examples of the richly hybrid culture of the United Sates-Mexico border. The border, conceived not as a line but as a space of mixtures and exchanges of all types (of goods, people, customs, languages), has attracted the attention of scholars and researchers for a long time.

Social work researchers are no different. For the past two decades, the Addiction Research Institute (ARI) at the School of Social Work has been conducting research on the border, focused on alcohol and drug use.

“The border is fascinating for many reasons,” ARI researcher Lynn Wallisch said. “From our perspective of substance use, we wanted to know if the border was its own place, with its own unique patterns, or if the Rio Grande is actually separating two different places.”

In 1996, at the request of the Texas Commission of Alcohol and Drug Abuse, Wallisch and colleagues Richard Spence and Jane Maxwell pioneered a large-scale prevalence survey of alcohol and drug use, abuse, and dependence among adults on the United States border. The survey included both urban areas and colonias—semi-rural, unincorporated communities characterized by lack of basic public services such as electricity, drinking water, and police protection. Another survey followed in 2003, to track whether the rapid demographic and economic changes in the area had an effect in patterns of substance use. And finally, in 2012, ARI researchers completed a path-breaking survey in collaboration with the Public Health Institute (Oakland, CA) that studied both the Mexican and United States sides of the border, as well as interior cities on each side. They are now in the early stages of analyzing this latest survey’s data, which provides the most comprehensive view of substance use on the United States-Mexico border so far.

What do these surveys say about whether the border is its own unique hybrid place, or two different places, one Mexican and the other American, separated by the Rio Grande?

“The answer so far has been… yes and yes,” Wallisch smiled.

Below are some of ARI’s findings about substance use on the border that explain what Wallisch means—and that might surprise you. For more findings and the surveys’ methodology, see this presentation (PDF).

1. Illicit drug use on the border is lower than in the United States as a whole

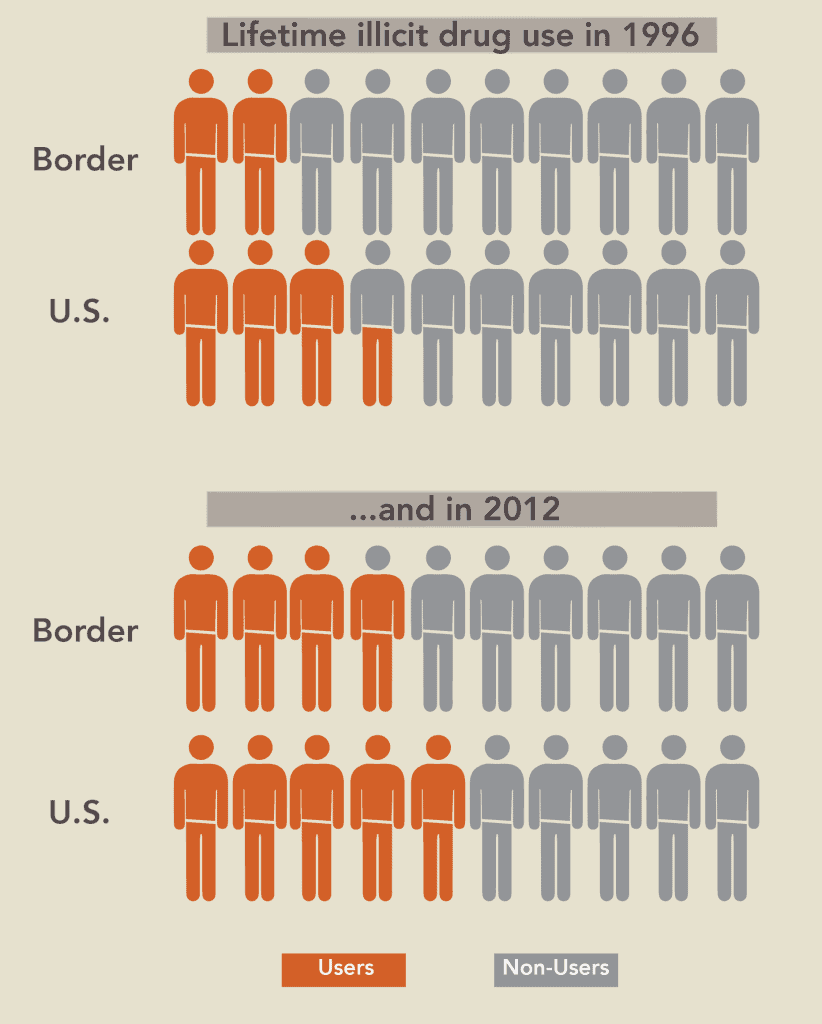

Figures on the graph to the right (click to enlarge) correspond to “lifetime drug use,” which is based on survey responses to the question “Have you ever used illicit drugs”?

Figures on the graph to the right (click to enlarge) correspond to “lifetime drug use,” which is based on survey responses to the question “Have you ever used illicit drugs”?

Although the graph shows that between 1996 to 2012 the percentage of people who report lifetime illicit drug use increased both on the border and in the United States as a whole, percentages for the border are lower at both points in time.

“Drug use levels are lower in Mexico than in the United States,” Wallisch explained. “Of course Mexican culture is very strong on the border, and a substantial percentage of the border population comes from Mexico. This might explain the lower levels of illicit drug use on the border that our surveys have found.”

More generally, Wallisch added, the lower levels of drug use in Mexico can be considered a protective factor against substance use on the border. Other protective factors are the presence of strong family and social support systems, religiosity, and the ‘immigrant advantage’—the fact that immigrants tend to be healthier, more resilient, and have strong work ethics and aspirations.

2. Misuse of prescription drugs is higher on the border than in the United States as a whole

17 percent of survey respondents on the border said they used prescription drugs “that were not prescribed for them or that they didn’t take as prescribed.” In the interior city on the United States side (San Antonio), only 9 percent reported misusing prescription drugs. And the figure for the United States as a whole is 6 percent.

“This finding might be explained by the fact that drugs for which you need a prescription in the United States are available without one in Mexico, and at lower prices. In fact, 45 percent of survey respondents said they had crossed to Mexico during the previous year to buy over-the-counter medicines or prescription drugs,” said Wallisch.

The most misused prescription drugs were pain relievers, which includes hydrocodone, oxycodone, codeine, morphine, and other opiates.

“The trend is of concern, although it might not indicate drug abuse per se” explained ARI researcher Jane Maxwell. “Because it is a legal drug, misusers might be unaware of potential addiction consequences. Once legal drugs become less effective or too expensive, misusers might turn to other opiates, such as heroin.”

3. But the border is not one homogeneous place

There are differences in substance use among border states, among main metropolitan areas along the border, between urban areas and colonias, and between the Mexican and the United States sides of the border.

There are differences in substance use among border states, among main metropolitan areas along the border, between urban areas and colonias, and between the Mexican and the United States sides of the border.

One interesting difference can be captured by looking at the drugs most used by individuals admitted to treatment and reported to the federal system.

The map to the right (click to enlarge) shows a west-east pattern, in which U.S. border states are more similar to their Mexican neighbors across the Rio Grande than to their U.S. neighbors to the east. Meth predominates in the western section of the border, and heroin and cocaine in the eastern part.

“This west-east use pattern along the border corresponds to trafficking patterns,” Maxwell explained. “Most of the methamphetamine has historically moved up from Baja California into California, and then spread eastward. Cocaine is much more prevalent on the lower, eastern part of the border, because it is trafficked across the Texas border into Houston or Dallas, and from there it moves eastward to the rest of the United States.”

4. And, at least regarding binge drinking, the border is no different from the interior

A measure of hazardous alcohol use is “episodic high-volume drinking,” more popularly known as “binge” drinking. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism defines binge drinking as a pattern of drinking that brings a person’s blood alcohol concentration (BAC) to 0.08 grams percent or above. This typically happens when men consume 5 or more drinks, and when women consume 4 or more drinks, in about 2 hours.

“The literature has described a drinking pattern of low frequency of drinking but high volume per occasion as characteristic of male drinking in Mexico, and as a culturally acceptable vehicle for male social bonding,” Wallisch said. “In Mexican cultures, sometimes this pattern is referred to as ‘fiesta drinking,’ because it occurs most commonly at parties or social events.”

ARI research shows, however, that when it comes to binge or fiesta drinking, the border is no different from the interior or off-border U.S. cities included in the survey. In 2012, the same percentage of border and off-border respondents (20 percent) reported binge drinking. Perhaps more interesting, this percentage is lower than the figure for the United States as whole (39 percent) or for U.S. Hispanics as a whole (35 percent).

“We were a little surprised to find that binge drinking was the same on and off the border,” Wallisch said. “However, our survey also showed that binge drinking was actually lower on the Mexican side of the border than in the Mexican interior. We need more research to figure out if there is something special about border culture that serves to attenuate the traditional pattern of fiesta drinking.”

Posted November 1, 2014. By M. Andrea Campetella. “Drugs” and “Alcohol” under Creative Commons license.