When it comes to sex ed in public schools, the country seems deeply divided between states who favor abstinence-only programs—26 of them—and states who favor more comprehensive approaches —18 states and the district of Columbia.

And yet, if we shift the focus from what we teach to how we teachstudents about sex, the divide is actually not that great.

At least that’s what social work researchers at the Texas Institute for Child & Family Wellbeing concluded after reviewing the evidence-based programs listed by the federal Office of Adolescent Health.

“All these programs, no matter if they are abstinence-only or comprehensive, use shaming language and are too focused on a prevention message that is negatively framed. The conversation is only around how to prevent pregnancies from happening, how to prevent STI’s from happening, instead of actually exploring what healthy sexuality looks like,” says researcher Jeni Brazeal.

In 2014 the institute applied for and received funding from the Office of Adolescent Health to provide sexual health education programming to Austin out-of-home youth—an umbrella term for youth in the foster care and juvenile justice systems.

The institute has a long history of working with this population in Texas, and had identified a need for sexual health education services for it. Youth in foster care change caregivers and schools often, so they might be missing sexual health education in the classroom. Foster care agencies and juvenile justice facilities might not be prepared to have these conversations with youth on their own. And they rarely receive services from community organizations because it is hard for them to meet the expectation that youth will be able to attend 75 percent of the sessions.

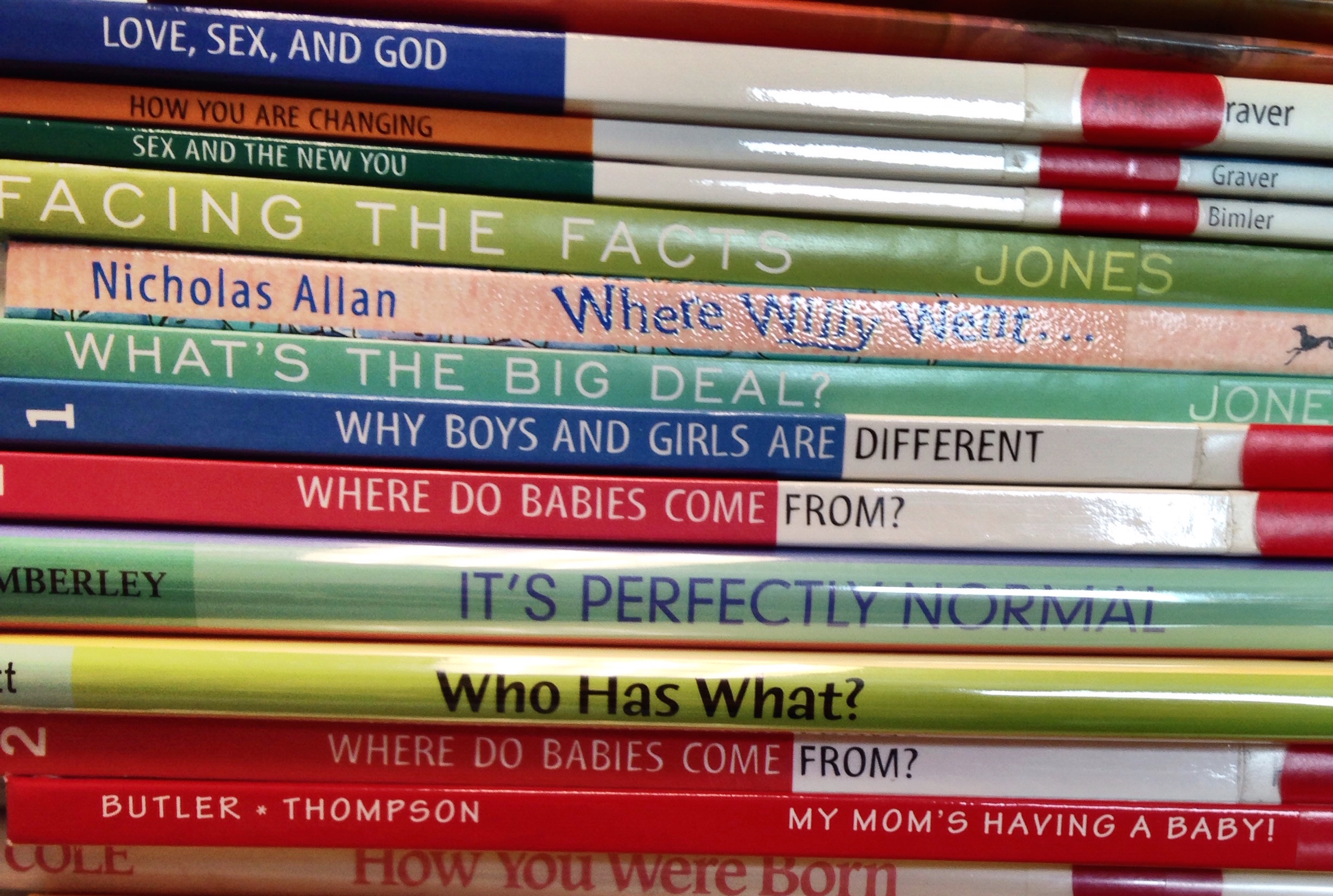

The similarities among the available evidence-based curricula, and their limitations, became clear as researchers reviewed them with out-of-home youth as the target population in mind.

“We were serving many teens who were already pregnant or parenting, and so the negatively framed prevention message does not really meet their needs. From the mindset of a teen who has been or is already pregnant, if we talk about sexual health only in terms of teen pregnancy prevention, the conversation is very judgmental and honestly, not very useful,” Brazeal says.

The team was also looking for curricula that were trauma-informed. Research has demonstrated that traumatic experiences have neurological, biological, psychological and social effects. Trauma-informed approaches recognize the widespread impact of trauma, integrate knowledge about it into practices, and actively seek to resist re-traumatization.

In the context of sexual health education, Brazeal explains, teaching from a trauma-informed approach means acknowledging that many people in the room have experienced some kind of sexual trauma, whether it is sexual abuse or stigma because of being pregnant, having an STI or identifying as a sexual minority. When teaching, the instructor makes all efforts not to re-stigmatize or re-traumatize people with any of these experiences.

“For instance, some sex ed programs use an analogy that virginity is like a piece of gum or candy bar,” says Monica Faulkner, the institute director. “The message is no one wants chewed up gum or unwrapped candy that’s been passed around, and the same goes with sex. Imagine how this message might come across to a young person who has experienced sexual abuse.”

In the end, the research team chose one of the available evidence-based programs and adapted it. They conducted a thorough revision of the language to make sure it was trauma-informed, and updated medical information and statistics that had changed since 2014, when the program was first released. They also added an anatomy lesson that used gender-neutral language and was inclusive of diverse sexual and gender orientations.

The overall goal, Brazeal explains, was to use this adapted program to pilot a sex-positive approach.

“Rather than employing shame or scare tactics, a sex-positive approach recognizes healthy sexuality as a natural part of being human, and encourages youth to consider their goals in life, what they need to achieve those goals, what it means to have healthy relationships, and what ideal parenthood looks like for them. We want them to feel empowered to make the choices they want for their future.”

The institute is now providing recommendations to the Office of Adolescent Health on how to best provide sexual health education for out-of-home youth.

Moreover, institute researchers argue that a sex-positive approach should be used beyond this specific youth population.

“We know that the available evidence-based programs, no matter if they are abstinence-only or comprehensive, are not really moving the needle in terms of changing youth attitudes and behaviors. So we need to rethink what we are doing in terms of sex ed for all youth, not only for out-of-home youth,” Brazeal says.

With this goal in mind, Faulkner has collaborated with Cardea Services to develop trainings on trauma-informed sexual health education. These trainings have been offered to more than 600 youth-serving professionals in Texas and beyond in the past year.

Brazeal clarifies that a sex-positive, trauma-informed approach—how to teach—is not necessarily tied to specific content—what to teach.

“If abstinence is part of the culture of the youth and their community, that’s fine. We just encourage youth-serving professionals to be careful about how they frame the conversation. If you say, you can’t have sex until you are married… well, you are going to have kids in the room whose parents are not married and who obviously had sex, so we want youth-service professionals to recognize that these statements carry a judgment that shames that family’s life.”

A sex-positive, trauma-informed approach, Brazeal explains, would instead frame the discussion on abstinence in terms of the youth’s own experience and values.

“The question we would ask the youth is, what is important for you to wait for? When is the right time for you to have sex? If their family believes that they should not have sex before they are married and they want to uphold that, that’s fine. Their values could also be to wait until after high school, or until after college, or until they are in a committed relationship… what is important is to help them process through this, clarify their values around sexual activity, and decide for themselves when is the right time.”

Posted September 29, 2016. By Andrea Campetella.